Introduction

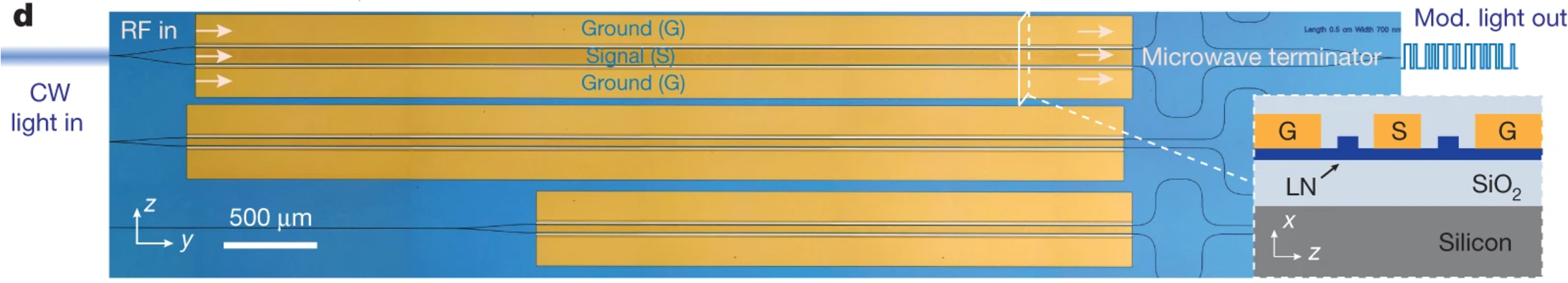

Traveling-wave Mach-Zehnder modulators based on thin-film lithium niobate enable high-bandwidth, low-voltage encoding of RF signals onto optical carrier waves, which is essential for realizing high-speed, power-efficient data communication. A typical traveling-wave Mach-Zehnder modulator is shown in the figure below1. It comprises a Mach-Zehnder interferometer with two waveguide arms and three electrodes for electro-optic modulation.

When designing such modulators, the geometrical parameters of the waveguide and electrodes should be carefully optimized to achieve a satisfactory tradeoff among insertion loss, modulation efficiency, and modulation bandwidth.

In this Note, I will introduce how to numerically calculate the insertion loss, modulation efficiency, and bandwidth of a lithium niobate traveling-wave Mach-Zehnder modulator. Our calculation is based on COMSOL Multiphysics2 and is verified by reproducing the results in the literature3.

Key Performance Indicators

The performance of a modulator is primarily quantified by optical insertion loss, modulation efficiency $(V_{\pi} \cdot L)$, and modulation bandwidth. An ideal modulator should have a low optical insertion loss, low $V_{\pi} \cdot L$, and a high modulation bandwidth.

For a Mach-Zehnder interferometer, $V_{\pi}$ is defined as the DC driving voltage that introduces a phase difference of $\pi$ between the two arms. The modulation efficiency of the modulator is defined as the product of $V_{\pi}$ and its length. A low $V_{\pi} \cdot L$ indicates a compact footprint and low power consumption, which are desired properties for most applications.

The output optical power of a modulator oscillates at the same frequency as the electrical driving signal, or the modulation frequency. This output optical signal is translated to an electrical signal by a photodetector, which has a spectral component at the modulation frequency. The power ratio of this spectral component to the electrical driving signal is defined as the electro-optic response. Importantly, the electro-optic response is a function of modulation frequency and usually decreases with frequency. The 3-dB bandwidth is defined as the modulation frequency where the electro-optic response decreases to half of the DC electro-optic response.

A high-performance thin-film lithium niobate modulator can achieve an insertion loss of less than 3 dB, a modulation efficiency around 2 Vcm, and a 3-dB bandwidth above 70 GHz.

Design Principles of Traveling-wave Mach-Zehnder Modulators

Lumped and traveling-wave Mach-Zehnder modulators

There are two types of Mach-Zehnder modulators: lumped Mach-Zehnder modulators and traveling-wave Mach-Zehnder modulators4. They share similar waveguide and electrode geometry, as shown in the figure. In a lumped Mach-Zehnder modulator, each electrode is connected to one probe, and the electrical signal propagates in the direction transversal to the waveguide. Since the propagation direction of the electrical signal is orthogonal to the optical signal, the interaction between them is weak. This phenomenon is especially prominent at high modulation frequencies, where the interaction between the RF and optical signals is further limited by the relatively short oscillation period of the modulation electrical signal. For this reason, the bandwidth of lumped Mach-Zehnder modulators is typically low (~several GHz).

For traveling-wave Mach-Zehnder modulators, the RF driving signal propagates in the same direction and at the same velocity as the optical signal. This greatly enhances the interaction strength between the RF signal and the optical signal, thereby reducing the driving power needed. Moreover, since these modulators are designed for velocity matching at high modulation frequencies, the electro-optic response can maintain a high value over a large bandwidth. Consequently, traveling-wave Mach-Zehnder modulators feature low driving power and high modulation bandwidth. In the following paragraphs, we will introduce how to design a high-performance traveling-wave Mach-Zehnder modulator.

Balance modulation efficiency and insertion loss

To achieve a low $V_{\pi} \cdot L$, we should place the electrode close to the waveguide, such that even a low bias voltage can induce a sufficiently large electric field around the waveguide. However, at a low electrode-waveguide distance, the electrode can also induce metal loss for the optical signal. Therefore, we need to find the electrode position where a satisfactory tradeoff between modulation efficiency and insertion loss is achieved. The typical metal absorption loss at the optimal tradeoff is several dB/cm.

In numerical simulations, the metal absorption loss can be extracted from the imaginary part of the simulated effective index5. The calculation of modulation efficiency, however, is a bit more complicated because it involves simulating the optical mode in a waveguide in the presence of an external electric field. Such a simulation can be conducted using COMSOL, and an example simulation file for calculating (V_{\pi} \cdot L) is available in this section.

Balance characteristic impedance, bandwidth, and fabrication cost

In addition to the location of electrodes, we also need to determine their geometrical dimensions. The geometry of modulator electrodes should be chosen for impedance matching, velocity matching, and affordable fabrication cost. Specifically, the characteristic impedance decreases with both the width and thickness of the electrode, and impedance matching requires a characteristic impedance of 50 Ohm. Velocity matching requires the effective index of the RF signal to match the group index of the optical signal. This is usually achieved by adjusting the thickness of the electrode. However, perfect velocity matching often necessitates an electrode thickness of more than 1 um, which comes with a high fabrication cost when the electrode is made of gold (Au). Therefore, sometimes we need to trade off velocity matching, and thus the modulation bandwidth, for an affordable fabrication cost.

Simulation Files

My COMSOL simulation files and codes for calculating the modulation efficiency and bandwidth of a traveling-wave Mach-Zehnder modulator are available using the following links. These simulations can reproduce the results in the literature with excellent accuracy. The computation method is introduced in detail in the corresponding readme.pdf file.

Wang, C., Zhang, M., Chen, X., Bertrand, M., Shams-Ansari, A., Chandrasekhar, S., … & Lončar, M. (2018). Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators operating at CMOS-compatible voltages. Nature, 562(7725), 101-104. ↩︎

He, M., Xu, M., Ren, Y., Jian, J., Ruan, Z., Xu, Y., … & Cai, X. (2019). High-performance hybrid silicon and lithium niobate Mach–Zehnder modulators for 100 Gbit s− 1 and beyond. Nature photonics, 13(5), 359-364. ↩︎

Ghione, G. (2009). Semiconductor devices for high-speed optoelectronics (Vol. 116). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ↩︎

https://optics.ansys.com/hc/en-us/articles/360034917493-Working-with-lossy-modes-and-dB-m-to-kappa-conversion ↩︎